|

To Print: Click your browser's PRINT button.

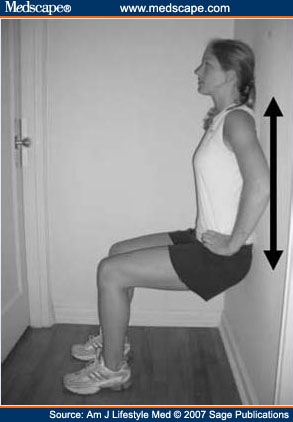

NOTE: To view the article with Web enhancements, go to: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/564335 State of the Art Review: Osteoarthritis and Therapeutic Exercise Todd P. Stitik, MD; Greg Gazzillo, MSIV; Patrick M. Foye, MDAm J Lifestyle Med. 2007;1(5):360-366. ©2007 Sage Publications, Inc. Posted 11/06/2007 Abstract and IntroductionAbstractTherapeutic exercise is an invaluable component to a comprehensive treatment program for patients with osteoarthritis. There are several major components to a complete therapeutic exercise program. Compliance with a long-term home exercise program after discharge from a physical therapy program is a very challenging but extremely important issue. Ideally, therapeutic exercise should be provided under the supervision of a physician who is knowledgeable in the use of exercise as a treatment for musculoskeletal conditions. Many practitioners of physical medicine and rehabilitation (physiatrists) can fill this important role for osteoarthritis patients. IntroductionOsteoarthritis (OA) can be a very debilitating disease that often adversely affects multiple aspects of a person's life. Osteoarthritis generally causes pain and discomfort in affected joints and therefore can lead to analgesic use, decreased mobility, and function and can have psychologic implications such as depression.[1] To help increase overall quality of life, a therapeutic exercise program should be incorporated into a patient's management plan. The use of therapeutic exercise as a nonpharmacologic treatment modality is generally accepted as efficacious.[2] Incorporation of the therapeutic exercise program can be conceptualized as occurring in several phases. The primary care physician (PCP) should strongly consider consulting a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician (physiatrist) to write the initial physical therapy (PT) orders (phase I), monitor the patient's progress during enrollment in PT (phase II), and transition the patient to a long-term home exercise program (phase III). The PCP can then resume monitoring this aspect of the patient's care once he or she is on a stable long-term home exercise program (phase IV). If circumstances change during the long-term follow-up phase, the physiatrist can then be reconsulted. Phase IAt the time of the initial physician visit, an assessment should be made of the patient with respect to the type of therapeutic exercise program that is to be provided. During the initial patient history, the physician ideally should inquire as to the level of exercise (if any) that a patient is currently performing and has performed in the past. Patients who are not exercising regularly at the time of the initial evaluation should be referred to a physical therapist. For those patients who are already actively engaged in an exercise program, the decision as to whether to refer the patient to physical therapy is dependent on factors such as patient motivation to continue with the exercises, patient willingness to modify exercises, and physician expertise with respect to exercise program design. In most instances, patients who are involved in an exercise program are probably still best served by a referral to a physical therapist to begin a physician-directed therapeutic exercise program because the patient's own self-initiated exercises were probably not created based on knowledge of OA pathophysiology and literature. Ideally, several individuals should work together, using a team approach for a therapeutic exercise program to be effective. First and most important is the patient, who must be motivated to increase his or her quality of life. Second, the physician should foster a trusting relationship with the patient. He or she must be observant to the limitations of the patient while developing an adequate exercise therapy program. This development involves frequent follow-up visits so that the program can be modified accordingly. Third, a physical therapist is often involved in starting the patient on the program. The therapist must be in tune with the patient so that a patient's physical limitations are not exceeded and the chance of exacerbation is minimized. Fourth, family members are often important to continually motivate, encourage, and help the patient reach his or her goal. Although the initial goal is for the exercise therapy program to be effective, a long-term goal is that patients will use this new knowledge and incorporate it into their daily lives. Personal trainers and/or exercise partners can also help with fostering the patient's long-term commitment to the exercise program. During the initial visit, several aspects of each exercise program should be discussed. Safety is of utmost importance. The physician must be able to identify the limits of the patient's ability. Using this knowledge, a program can be tailored so as not to worsen the condition. Proper demonstration of every exercise should ideally be done in person. This can prevent improper execution, as the patient will have been taught to continue the exercise at home. Patients should be educated to avoid complications during the program. This includes avoiding overexertion and extreme joint flexion, balance between rest and activity, controlling their weight and eating sensibly, and respecting pain. Finally, a schedule of adequate follow-up should be discussed, which serves several purposes. The physician can keep track of the patient's status from baseline. Change of the program can then accommodate the patient's progress. Short- and long-term goals can be reinforced. It will also give opportunities to instill confidence and motivation into the patient. Components of a Therapeutic Exercise ProgramThe specific PT orders should ideally be individualized based on multiple factors from the history, physical exam, diagnostic test results, and extent of the physical therapy coverage by a patient's insurance. There are several components of a comprehensive therapeutic exercise program for OA patients. These include range of motion (ROM), stretching, strengthening, and aerobic conditioning exercises. It is important to implement integrated components of each of these to achieve the greatest gains toward the patient's therapeutic goals. The program should not be static. Instead, the program should be altered in accordance with the patient's progress. Range-of-Motion ExercisesMaintaining joint ROM is important to counter OA's tendencies toward progressively worsening ROM. Patients with OA generally have a decrease in ROM due to pain and/or loss of flexibility within the osteoarthritic joint. This can have dramatic adverse effects on a person's function. For example, a loss in hip and/or knee flexion can limit a person's ability to climb stairs and can change his or her gait pattern.[3] Exercises to maintain and even improve ROM should be done on a regular basis. Range-of-motion exercises have been shown to decrease discomfort and pain, which can increase function and overall independence.[4] It is crucial that ROM therapy be tailored to the individual, as there can be significant differences among OA patients. Patients who cannot complete a full ROM, due to either motion limitation or inadequate strength, should be assisted by the therapist. This is referred to as an active-assisted ROM exercise, whereby the therapist would help complete a full ROM. Individuals who do not have such limitations can perform active ROM exercises on their own. A continuous passive motion (CPM) device can also be used to mechanically facilitate ROM. The patient does not activate any muscles as the machine passively moves the joint. In 1 study, 21 hip OA patients underwent a therapy using CPM. The results showed that patients had improvements in pain and self-selected walking speed, as well as a decrease in analgesic use.[5] However, CPM devices are currently only clinically used with OA patients who have undergone total joint replacement (TJR) and are in the acute phases of rehabilitation. They are not currently generally used during non-TJR rehabilitation. Stretching ExercisesMost OA patients have some degree of inflexibility due to either shortened muscles and/or intrinsic joint restrictions. Stretching exercises can help prevent this and have been shown to increase overall ROM. For example, increased range of hip abduction after a stretching program was found in patients with hip OA.[6] All muscles that cross the affected joint ideally should be stretched on a daily basis. Muscles should be initially warmed up, as this enables collagen fibers to be maximally stretched.[7] Discomfort and excessive force may adversely affect the joint or target muscle(s) and should be avoided. In addition, bouncing the joint when stretched (aka ballistic stretching) is not ideal. Stretching should be slow, and there should be gradual movement within the allowable ROM to the point where slight resistance is found. This position should be held for at least 30 seconds and ideally repeated 3 times per day.[3] Many different stretching exercises have been described for most major muscle groups.[8] Some examples of stretching hip-girdle and knee region muscles are described below (Figures 1-3).  Figure 1.  Figure 2.  Figure 3. Strengthening ExercisesClinical studies have shown that strengthening the muscle groups around the affected joint is effective and important in treating OA patients, especially those with hip and/or knee OA.[9] Strengthening exercises have been shown to increase not only muscle strength but also muscle endurance and contraction speed.[10] In 1 study, hip OA patients who underwent an exercise program had a greater decrease in pain after 3 months compared with a group with only standard care.[11] Other studies have shown that quadriceps strengthening in knee OA leads to improved strength, function, and pain, as compared with a control group.[12,13] Weight-bearing exercises have also been found to be important for proper cartilage nutrition.[14,15] Some physicians (including the senior author [TS]) believe that each muscle group should only be strengthened a maximum of 2 times per week. This schedule allows for an adequate period of rest so that the muscle can recover between strengthening sessions. Exercises that can be incorporated into an OA patient's exercise program are described below. Quadriceps weakness has been consistently demonstrated in knee OA patients[16-18] and has been correlated with knee pain.[19] Again, it is important to tailor the exercise to the patient's ability. Those who have very limited initial strength can perform low-level quadriceps strengthening exercises. These include "quad sets" and "straight leg raising" (Figures 4 and 5). Patients with a moderate amount of strength or those patients who have progressed beyond quad sets and straight leg raises can do wall slides (Figures 6 and 7).  Figure 4.  Figure 5.  Figure 6.  Figure 7. Finally, more vigorous strengthening of the knee can be accomplished with a leg press. Patients can increase the amount of weight as needed to facilitate their therapy. Wall slide and leg press exercises are examples of closed-chain kinetic exercises, whereby the distal limb (foot) is in direct contact with a surface (floor, leg press machine). This contact can be thought of as helping to dissipate forces acting on the knee by spreading these forces out along the entire kinetic chain from the ankle distally to the spine proximally. In contrast, in open-chain kinetic exercises, the distal limb is not in direct contact with a surface. An example of this exercise is the leg extension machine. It has been shown that open-chain kinetic exercises can significantly increase forces within the knee to pathologic levels. These include tibiofemoral and patellofemoral compressive forces, as well as tibiofemoral shear forces.[20-22] It is for these reasons that open-chain kinetic exercises should probably not be included in most OA patients' therapy programs, other than perhaps straight leg raises to build initial strength in a patient who is only capable of low-level quadriceps strengthening. Aerobic ExerciseThe 2000 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines for the medical management of knee and hip OA recommend and encourage incorporating aerobic conditioning into the therapeutic exercise regimen of patients with OA.[2] Aerobic conditioning is believed to be safe and effective.[23] Patients with OA have been shown to have a lower aerobic capacity than the general population.[24] Therefore, implementing aerobic exercise should also be beneficial to the overall health of the patient. Several mechanisms for how aerobic conditioning helps OA patients have been proposed. One is that it causes the release of endogenous opioids, thereby reducing pain and symptoms of depression and anxiety.[22,25,26] Other proposed mechanisms include reduced morning stiffness, improved balance, and increased walking speed.[27] Land- and aquatic-based aerobic programs have been implemented into the exercise programs of OA patients. Studies involving land-based and aquatic aerobic exercise have shown these to be beneficial for OA patients.[28,29] Factors to consider when prescribing a particular aerobic exercise include the patient's cardiovascular level, preference, and accessibility of exercise equipment. For example, many YMCAs offer aquatic exercise programs through the Arthritis Foundation.[30] For some patients, this is an ideal scenario due to the group setting, high level of expertise in the instructors, and the very low impact that water exercises cause (given the buoyant effect of water). For all aerobic exercises, patients should first strive for a target age-predicted heart rate of approximately 70% of (140 - age) and gradually increase it to a maximum of 85% of (140 - age). Another factor to consider when recommending aerobic exercises is the desirability to cross-train (ie, incorporating several different aerobic exercises into the patient's program). Cross-training can help to prevent the musculoskeletal overuse injuries that can occur when the same exercise is performed repeatedly. Cross-training can also prevent the boredom that can occur if the same exercise is performed over time. Finally, the beneficial effects on the body are likely to be greater if variety is introduced into the program as exercise variety should lessen the probability that the body will simply adapt to the exercises being performed. Phase IIWhen the patient returns for the physician follow-up visit after completing the originally ordered PT, a progress summary note should be provided by the therapist and reviewed by the physician. This summary note ideally should describe several aspects of the therapy, including the therapeutic exercise component to date. Physical therapy progress notes often vary significantly with respect to quality and content. Although some notes concisely summarize the patient's progress and make recommendations regarding the need for further PT or discharge to a home exercise program (HEP), other notes are either so detailed that the main message is lost or are simply a daily treatment note that only describes the treatment rendered on a given day. Given this significant heterogeneity, the physician should consider creating his or her own progress report template and sending this with the patient in order for it to be completed just prior to the physician follow-up visit. Figure 8 is an example of such a report that is used by the senior author (TS) for all patients (including OA patients) that he sends to PT.  Figure 8. The physician and patient should discuss the report to gauge the patient's perception of it and to determine if the patient is in agreement with the therapist's recommendations. Ideally, if there is a consensus among the patient, physician, and therapist that PT should continue, continuation orders should be written. Within these orders, the physician should make any revisions to the program that he or she believes is necessary. If consensus regarding the need for continued PT is not reached, the physician should use his or her best judgment in coming to this decision and should explain the rationale to the patient. Phase IIIA long-term goal is for the patient to continue performing the exercise program on his or her own after discharge from PT or another supervised exercise program. Once the physician discharges the patient from PT, an effort should be made to facilitate transition to an HEP. Patients can continue to exercise either at home or in a community exercise gym, depending on preference and resources. Incorporating this into their lives will likely be of long-term benefit, as 1 study showed improved physical function of patients with knee OA and exercise compliance.[31] Ideally, customized programs should be designed for every OA patient. This has the added benefit of promoting an increase in compliance.[32] Phase IVOnce the patient is regularly performing the HEP in the early stages after discharge from PT, some plan should be put into place to maximize the probability that he or she will be compliant with this over the long run. Compliance is a key factor in continuing to receive positive benefits from exercise. However, long-term exercise compliance in OA patients has been shown to be poor. One study found only a 50% compliance rate in a population with knee OA after 18 months, despite frequent phone calls and even home visits to monitor exercise compliance. These patients had previously been enrolled in a supervised exercise program and had benefited from it.[33] The benefits of exercise have also been shown to decrease when the exercise program has declined.[34] For these reasons, it is important to incorporate strategies to increase compliance. Exercise diaries are an effective way to tabulate progress so that patients can see results. Especially if the results are positive, this can encourage the patient to continue. Support from different groups of people can increase compliance as well. These include family members, personal trainers, and exercise partners. ConclusionTherapeutic exercise is likely to help with the signs and symptoms of OA. It should improve a patient's overall quality of life and function. This is in large part due to a decrease in joint pain, therefore decreasing the amount of analgesic use; an increase in joint flexibility and mobility; an increase in strength and stamina; and lasting psychological benefits.[35] Exercises that are integral to a solid program include ROM, stretching, strengthening, and aerobic conditioning exercises. It is the motivation and determination of the patient that will drive success. Proper education must be given to the patient to maximize benefits in the short and long term. This includes demonstration of performing each exercise in person, which will give the patient knowledge to perform them after discharge and will avoid complications as well. For the benefits of the exercise program to continue, an OA patient should perform the program long term either at home or in a community-based gym. Compliance is a major problem and should be addressed. Techniques such as a diary, exercise partners, discussions about exercise during follow-ups, and motivation from family members, exercise partners, and personal trainers can be used to facilitate compliance. References

Reprint Address Address for correspondence: Todd P. Stitik, MD, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-New Jersey Medical School, 90 Bergen Street, Suite 3100, Newark, NJ 07103; e-mail: stitikto@umdnj.edu Todd P. Stitik, MD, Greg Gazzillo, MSIV, and Patrick M. Foye, MD, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-New Jersey Medical School |